Partner content in association with

How the pandemic unlocked the digital economy across all of Indonesia

The East Ventures Digital Competitiveness Index is an early sign that Indonesia’s digital economy is poised to expand significantly beyond its urban centers, backed by active interventions from the government, corporates, investors and startup founders

The trajectory of any significant social, cultural, or economic development has traditionally moved in one direction – outward from the metros. Especially in countries with a large geographic spread like Indonesia or India, life-altering shifts in the way people work and live invariably take time to percolate to the hinterlands.

The digital economy is a notable exception. While its impact was first felt in the metros, it is expected to ramp up with an unprecedented rapidity. In Indonesia, it is being powered by the spread of telecom infrastructure, inexpensive data, and economically priced smartphone handsets.

Conducted by East Ventures, the East Ventures Digital Competitiveness Index (EV-DCI) is a study that tracks the spread of the digital economy. The EV-DCI was created after extensive interviews with ministers, local governments, key regulators, giant corporate leaders and startup founders.

The median EV-DCI score has risen from 27.9 in 2020 to 32.1 this year and points to a greater degree of parity than ever before, when it comes to digital competitiveness among provinces in Indonesia. While the current data principally covers the metro areas, it signals to the vast potential of rural Indonesia, which is just starting to be tapped. It is estimated by East Ventures that rural Indonesia represents a digital economy that will be manifold the size of its urban counterpart.

Willson Cuaca, co-founder & managing partner East Ventures said, “There are more than 202.6 million internet users in Indonesia – 73.7% of the population. However, the question we pressed into was whether these 202.6 million have gained the same benefits from digital acceleration. When almost every headline was fixated on the rapid growth of the digital economy, we took the question one step further and asked: How equal?”

The study measures 9 pillars that directly or indirectly relate to the development of the digital economy in Indonesia. The most significant factors considered are infrastructure development and the increase in spends under information and communications technology (ICT). The other pillars considered include human resources, entrepreneurship and productivity, finance as well as regulation and the capacity of the regional government.

What makes the uptick in the EV-DCI noteworthy is the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, with economies and citizens all over the world, still coming to grips with its lasting impact. However, while the pandemic initially slackened the pace of growth in Indonesia, it has ultimately given a fillip to the adoption of digital services.

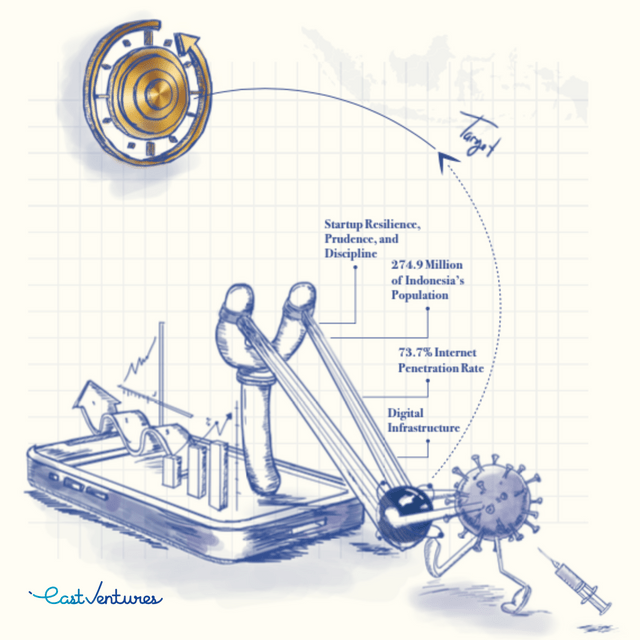

Cuaca said, “Like a slingshot that is being pulled backward, Indonesia’s digital economy will be ready to propel faster toward its golden era, after the pandemic has subsided.”

Indonesia’s golden era

There is ample evidence that this golden age will not be a merely Jakarta or Java-centric phenomenon. Cuaca said, “In our pilot edition, published last year, we found that the digital economy in Indonesia was still concentrated in Jakarta and provinces in Java, with a huge gap among the most and the least competitive regions.”

This time around, there have been some significant shifts, even as the 10 most competitive provinces remain the same. In 2020, the top six positions were all provinces from Java, with DKI Jakarta in first place. However, Bali and Riau Islands have seen an encouraging increase in their scores. Bali is now at 4, a leap from its 2020 position at 7; while Riau Islands has moved to 7 from 10 last year.

Bali’s performance can be attributed to a high level of digital infrastructure development, including a rise in the number of villages with 3G and 4G connectivity. When it comes to Riau Islands, geography is certainly a factor, particularly its proximity to Singapore. This makes Riau Islands, especially Batam, one of the top investment targets for Singapore-based firms.

A recent example of such an investment is the Nongsa Digital Park (NDP), a designated special economic zone, the result of a collaboration between the Indonesia and Singapore governments. The NDP is a “digital bridge” between Singapore and many of the fast growing players in the sector in Indonesia.

Singapore’s Economic Development Board (EDB) has invited investors to locate digital-related businesses in NDP which currently hosts around 150 companies and 1,000 developers and employees in the creative industry. It allows Indonesians to benefit from job openings at tech startups and multinational firms that had previously made Singapore their base. The companies with tech talent at Nongsa include AIA, FWD and WebImp, with more expected in the future.

In addition, lecturers from Singapore Polytechnic help their peers at Batam’s Polytechnic department with skill enhancement programs in software engineering and big data programming.

Chng Kai Fong, managing director at Singapore Economic Development Board said, “NDP allows Singapore-based companies to develop their services and products by leveraging the talents of the tech-savvy and dynamic young generation in Indonesia.”

The rising tide that lifts all ships

The expansion of the digital economy has led to a surge in spending across services. The EV-DCI 2021 reveals that besides the average spend on ICT tracking northwards, wages and service fees for workers in the sector are also on an upwards trajectory.

The disintermediation offered by several Indonesia-based startups gives more opportunities for small businesses to directly reach their customers. It took Tokopedia a decade to onboard 7 million merchants on its platform, but the pandemic has seen an addition of 2.5 million new sellers. Logistics platforms too have registered sizable growth, to take on the challenge of distribution. Waresix now has 40,000 trucks and 375 warehouses across 200 cities in Indonesia.

Another facet that’s led to the growth of the digital economy is the reluctance of startups to be saddled with business models that are losing relevance. After initially being severely affected by the lockdowns and restrictions on mobility, Traveloka shifted tracks to super-serve the domestic tourism industry. Micro-retail firm Warung Pintar expanded its operations to support over 230,000 warung owners in 65 cities in 2020.

It’s not just the breadth but the depth of the digital economy that has grown in a post-pandemic world. While the usual suspects like ecommerce and food delivery were expected to perform well, there has been a rise in the demand for services like telemedicine, virtual meetings, and digital transactions. A significant emerging sector is edtech: Ruangguru’s free online class has now helped over 10 million Indonesian students keep up with their lessons even as schools remain closed. The edtech platform now has 22 million students.

Unlocking the true digital potential of Indonesia

The expansion of the digital economy is an example of an ecosystem including governments, VCs like East Ventures, corporates, and startups working in lockstep to ensure that as many Indonesians as possible stand to gain. Cuaca said, “This report highlighted the pivotal role of synergy amongst varying stakeholders in developing the overall tech ecosystem in Indonesia, particularly during a crisis.” The role that the government has played in ensuring that Indonesia fires on all cylinders is significant.

Speaking about EV-DCI 2021, the Minister of Finance Sri Mulyani said, “The acceleration of digital economic transformation has been a priority in the state budget so that we can finance the development of digital infrastructure, provide accessible internet for all, and increase the quality of human resources.”

There was a significant push towards getting MSMEs to embrace digital. With nearly 90% of MSMEs in West Java affected by the pandemic, the local government rolled out capital assistance via a QR-code based payment system. The pandemic saw a 40% growth in digital economic activities. Ridwan Kamil, Governor of West Java expected this growth trajectory to continue, driven by pandemic-induced digital lifestyle and said, “There will be extraordinary stories from West Java about how, from rural to urban areas, the economy was lifted, because of the Digital West Java vision: Smart City in the urban areas and Smart Village in the rural areas.”

The local government worked with e-commerce sites to facilitate tax payments resulting in a spike in revenues. The Village Digital Center was established in collaboration with Tokopedia to digitally market local products. Educating micro and small, medium enterprises in the use of digital technology has helped both the businesses themselves as well as their consumers.

This would of course have been impossible without adequate infrastructure. Coordinating Minister of Economics Airlangga Hartarto said, “We supported the fibre optic development from the Western to Eastern parts of the country. Then, we broadened the reach of the connectivity of multifunctional satellites or Satria satellites to the Eastern part.” In West Java, for instance, free Wi-Fi was installed in around 700 villages. These measures have made Indonesia an even more attractive destination for global tech giants such as Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud and Microsoft.

Returning to his slingshot metaphor, Cuaca said, “Once the pandemic is properly under control, Indonesia can release its grip and launch the digital economy into its golden era. We hope it will take everyone along – not only those in Jakarta and Java island, but also all of the people across Indonesia’s 34 provinces.”

This article was created in collaboration with East Ventures. A full copy of EV-DCI 2021 is available for download at east.vc/dci